The Australia-US Free Trade agreement gave a lot of people the shits. It gave economists the shits, because the important issues got lost beneath ass lickers and a politician licked for his deployment of dangerous metaphors. It gave US haters the shits because we gave preferential treatment to the nation that they think is most undeserving. And it had the Australian media shitting itself, because it threatened to offer Australian consumers the option to switch onto superior US entertainment.

The important thing to remember from the debate is that no respected economist said the deal would make Australia worse off. There was a lot of argument about the size of the benefit, but no respected economist said that it was a bad deal. It could be added that, given the rise of US protectionism, the deal also had some extra value as it set down minimum standards for Australia’s access to the US market.

The trade numbers for the first ten months of the AUSFTA gave some satisfaction to the deal haters – where credible economists could/would not. They showed that Australian exports to the US had fallen, and that Australian imports from the US had increased. Haters were quick to conclude that the trade deal had proven itself to have been a bad idea (here).

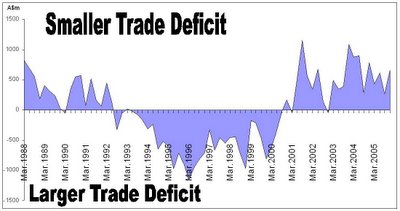

Full year data takes some of the sting out of the criticism. A pick up in Aussie exports in the final quarter has reduced the gap between 2004 and 2005 exports to 3%, from 3.8%. Because trade tends to be heavy in Q4, the Australian deficit with the US looks worse for the full year than for the first three quarters – it is A$1159m larger than 2004, whereas it was A$913m after the first three quarters. However, in percentage terms, the AU/US deficit is now 10.6% larger than in 2004, whereas it was 11% larger after the first three quarters.

So what are the facts?

1. Australia’s trade deficit with the US was A$12.1bn in 2005. This is a little larger than the average for the previous 5 years, which is A$11.1bn.

2. Exports to the US were A$9.3bn in 2005, 3% less than in 2004, and 13.4% less than the average for the previous 5 years. The US took 6.7% of Australia’s exports in 2005, down from an average of 9.2% for the previous 5 years.

3. Imports from the US were A$21.4bn in 2005, 4.3% more than in 2004, but 1.6% less than average for the previous 5 years. The US provided 13.7% of Australia’s imports in 2005, down from an average of 17.2% during the previous 5 years.

4. On both the import and (especially the) export side, the US is becoming a less important trade partner. The proportion of Australian exports headed for the US has declined in each of the past five years - from 10% in 2000 to 6.7% in 2005. The proportion of imports arriving from the US has also fallen each year since 2000 – from 19.8% in 2000 to 13.7% in 2005.

5. In 2005, the US was the largest source of Australian imports – though China was a close second, and will almost certainly take first place in 2006. The US was our 4th largest export market, after Japan, China and South Korea, in that order.

6. In 2005, the Australian dollar was 3.4% stronger against the US dollar than in 2004 – making Australian exports more expensive, and hence less attractive in US dollar terms. The flip-side is that US imports are cheaper, and hence more attractive to Australians. The Aussie dollar is 25.5% stronger against the US dollar than the average for the past five years.

7. As Australia buys significantly more from the US than it sells to the US, all things being equal, the US has to grow faster than Australia to keep the trade deficit from increasing. Since 2000, real Australian GDP has grown by 17.8%, 4.2 percentage points more that US GDP, suggesting that the deficit should be widening. Remarkably, the trade deficit in 2005 was unchanged from that in 2000 (12.1bn); however as noted in point 1, the 2005 deficit is 1bn larger than the average for this period.

8. Australian imports from the US are mostly capital and intermediate goods. Data for the last 7 months of 2005 show that 34% of imports were capital goods, another 20% were parts for these capitals goods, and another 25% were other intermediate imports such as industrial supplies. The boom in investment has increased the demand for these goods, and the US, as the world’s leading manufacturer has supplied them.

While trade is a complex game, something a little more interesting can be said about trade flows with the aid of a simple (or naïve) trade model that controls for exchange rates and the level of GDP. Broadly speaking, in 2005 Australia did better than could be expected, given the relative strength of the US and Australian economies, and the strong Aussie dollar. Once we control for GDP and the currency, some interesting observations emerge:

1. Imports from the US are about A$1.7bn less than could be expected.

2. Exports to the US are about 300m more than could be expected.

3. As a result, the trade deficit for 2005 is almost A$2bn better than could be expected.

It follows that the trade deficit with the US might get wider due to the ‘natural’ forces of trade, as Australia’s run of good (trade) fortune comes to an end and a more normal state of affairs is restored. It is therefore highly speculative, and dubious, to argue that an increase in the trade deficit is proof that the free trade agreement is a bad deal for Australia, simply because the deficit is getting wider. The strength of the Australian economy and currency suggests that we should be exporting less to the US, and importing more from the US.

I do not, however, expect that the trade balance is going to get worse in the near term. Leading capex surveys suggest that investment will slow or decline in 2006, so imports of capital equipment will probably also decline. If this happens, Australia will probably import less from the US, and the deficit will close.

The free trade agreement may, however, make the trade deficit with the US worse – if it increases investment. Economists agreed that one of the most beneficial elements of the deal was the scaling back of the foreign investment review board’s oversight of US investment in Australia. This was expected to significantly increase US investment in Australia. Increased investment will require increased capital imports, which will no doubt come from the US, and make the trade deficit wider than it otherwise would’ve been. An increase in the deficit as a result of this sort of investment is not, however, a bad deal for Australia.

2 comments:

I don't agree with your use of the term 'better' when referring to a reduction in the trade deficit. A trade deficit is not bad on its own. I run up a massive trade deficit with the local Woolworths but it would be ludicrous of me to get a job there just so I can 'improve' my trade position.

A trade deficit can only be better or worse if it is moving in directions that result from traders better taking into account the costs of exports and imports. The FTA will remove tariffs, removing a price wedge and in that way improving our trade position.

However, it will also distort the price of importing from the US relative to imports from non-preferential countries. Thus, the deficit might get worse because we start importing goods that are not least cost.

Because these effects work in opposite directions your figures can't determine whether things are getting better or worse. Yet, the surge in imports does not bode well for the real size of the trade diversion effect.

I don't either, in the strict sense that you mean it. however, rather than a article that went over the tired riccardian road of demonstrating that surplus does not mean good, and deficit does not mean bad, i chose to pitch the story in the language that people understand.

You can read better as smaller and worse as wider in the last few paragraphs with no loss of meaning.

The point i wanted to make is that the deficit with the US is smaller than we might expect at present - especially given the size of the mining / investment boom. The surge in US imports has been largely capital goods, and i'd sooner attribute the increase to the high level of Aust capex than trade distortion.

Post a Comment